Three Delays and the Stroke Care Pathway in China

September 1, 2016

Abstract

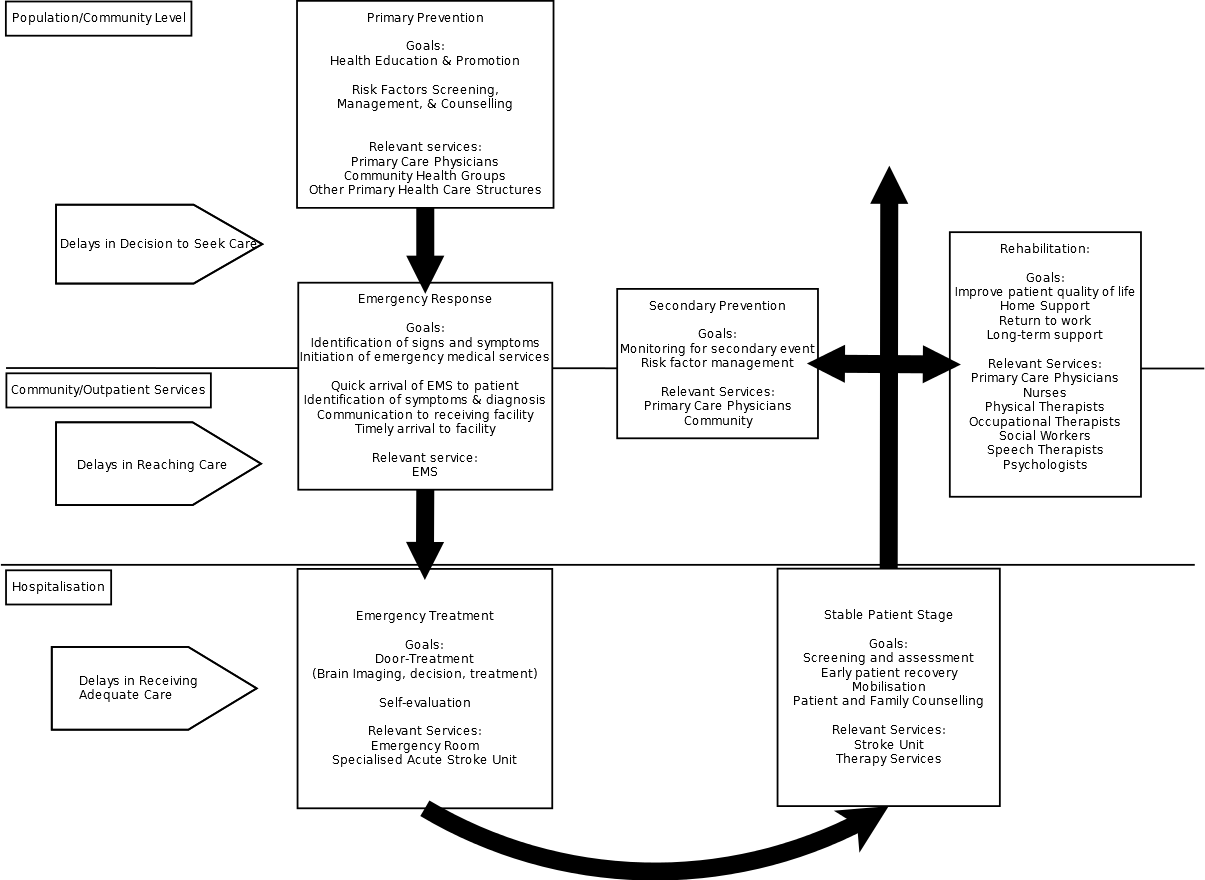

Stroke is one of the leading causes of death and disability in China. China’s Stroke Registry estimates that China will face 2 million new stroke cases annually. The purpose of this literature review is to critically look at China’s ability to handle a stroke emergency. This emergency has clear time constraints based on the effectiveness of thrombolysis – otherwise known as the “golden window.” Because of this time-sensitive nature, the three delays model which was originally developed for maternal mortality has been adapted to help investigate factors prohibiting stroke patients from meeting the time for treatment. The “delay in the decision to seek care” is an exploration of the factors affecting care-seeking behaviours and health service utilisation at the individual/patient level. “The delay in reaching care” depends on the infrastructure of emergency health services in the prehospital setting. We discuss the development of the emergency system, its present state and how its current organisation affects stroke emergencies specifically the onset-to-door time. Finally, “the delay in receiving adequate care” looks at the organisation of Chinese emergency departments and examines the factors preventing timely treatment, clinical pathways, and quality improvement mechanisms. The stroke care pathway, a diagram of all the services relevant to stroke care, serves as a framework that allows us to see how these distinct pieces of China’s health system interact. What are the challenges and barriers to implementing a comprehensive stroke care pathway in China? And how can China’s health system improve itself to face the growing urgency that is stroke?

Introduction

Since the dawn of the epidemiological transition, many countries have seen the rise of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). The theory of epidemiological transition, first defined by Abdel Omran in 1971, refers to the pattern where the country’s development corresponds to a change in disease burdens – from communicable diseases to noncommunicable diseases. Along with the consequences of socioeconomic changes and demographic changes such as a greater proportion of aging populations, WHO’s Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014 has reported that stroke has jumped to the front as the leading cause of death and disability (WHO 2014). By 2020, it is estimated that there will be 25 million global annual stroke deaths, and 19 million of those deaths will be in developing countries (Walker et al. 2014). In order to properly tackle this disease, a wide spectrum of health services from prevention to treatment and rehabilitation will need to be provided. Burden and mortality caused by cardiovascular diseases that heretofore were most prevalent to western countries have now increased in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), having the majority of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost due to stroke – LMICS accounted for 64% of total DALYs for ischaemic stroke 86% of haemorrhagic stroke (Krishnamurthi et al. 2013). Today many of the LMICs make up a global stroke belt – a term first used by the United States to describe an area containing a high incidence of stroke (Kim et al. 2015). And while mortality rates caused by stroke has largely decreased globally, findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 reveal that the incidence of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke has risen by 37% and 47% respectively (Krishnamurthi et al. 2013). This means that many health systems will have to prepare for an onslaught of stroke survivors. Considering that a third of patients who suffer from stroke will have disabilities from physical to mental and will require continued support, it is exceedingly critical for countries to develop strong health infrastructure around stroke care and to make available support services. Costs associated with complications from aftermath of a stroke can be immense sometimes requiring significant resources to support the patient for the remainder of their lives. However, health systems of LMICs are well behind compared to those of high-income countries, and lessons are hard to transfer as the capacity to provide care between countries can vary widely, so many will have to approach the problem in their own way.

In the People’s Republic of China, where cerebrovascular diseases have ranked 2nd and 3rd in mortality in rural and urban respectively, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have become a national priority (China Statistical Yearbook 2015). Findings from the Chinese Stroke Registry also agree – ranking stroke as one of the leading causes of death and estimating 2 million new stroke cases annually as well as 7.5 million current stroke survivors (Liu et al. 2011). From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, stroke is the primary cause for years of life lost (YLLs) in China, the indicator for premature death (IMHE 2016). It is one of the top three causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2010 (GBD 2010). The rates for haemorrhagic stroke at 20-30% of total stroke in particular are higher than that of western countries at 13.9% (Jia et al. 2009). Within the country, there is a disparity in stroke mortality rates between urban where rates have decreased and rural areas where rates have stayed the same over a two-decade period (1987-2001), thereby demonstrating inadequacies in care in rural parts (Zhang et al. 2007).

A rapidly developing China and increasing middle class raise concerns about how the country might sufficiently address the risk factors for stroke in the future. All of this is complicated by the sheer size and diversity of the country with different health priorities. China also possesses its own stroke belt, encompassing the regions North and West of China where large cities have seen rising rates of hypertension and obesity (Xu et al. 2013). Trends in population such as the movement of adults seeking work in large cities resulting in left behind children and elderly also affect health priority setting for certain districts. China boosts around fifty ethnic minority groups, and studies are underway to determine whether specific groups are predisposed to stroke or even to the risk factors of cerebrovascular diseases (Wang et al. 2013). Today, China has increasing rates of obesity with 13% being in urban areas and 85% in being rural regions and has one of the highest male smoking rates in the world (Liu et al. 2011). The generalisabilty of interventions also poses a major challenge as differences in socioeconomic status, geography, and culture will mean conclusive results will be difficult without large scale studies. Risk factors such as smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy diets, and environmental pollution will require smart strategies on the part of policymakers. Equally pressing are concerns about China’s ability to provide equal to access to stroke services across the country. Although the country has expressed a commitment to addressing inequalities of access in more rural and remote areas, disparities in care still persist, and the country is struggling to allocate its limited resources.

Policy Background

To help address the urgency of stroke, the World Health Organization has provided a comprehensive list of policy guidelines such as the Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013-2020; Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; Global Status Report on NCDs 2010; Global Capacity Assessment on NCDs 2010. While the primary prevention of stroke and management of risk factors of cardiovascular diseases are its main messages, the WHO has outlined several strategies for treatment and care during an emergency and in the aftermath of stroke. The WHO has been deliberate in describing its solutions as feasible and cost-effective. Most of the interventions for reducing NCDs was listed as a “Best Buy,” where a core package of interventions was predicted to be able to significantly reduce the number of premature deaths associated with NCDs (WHO 2013). Nevertheless, there are obvious differences between this idealized planning and the actual implementation of such guidelines – the discrepancies that will be surveyed in the following chapters. Obviously, what needs to be examined is how these standards are translated to the national level to the local level down to the individual patient and everything in between.

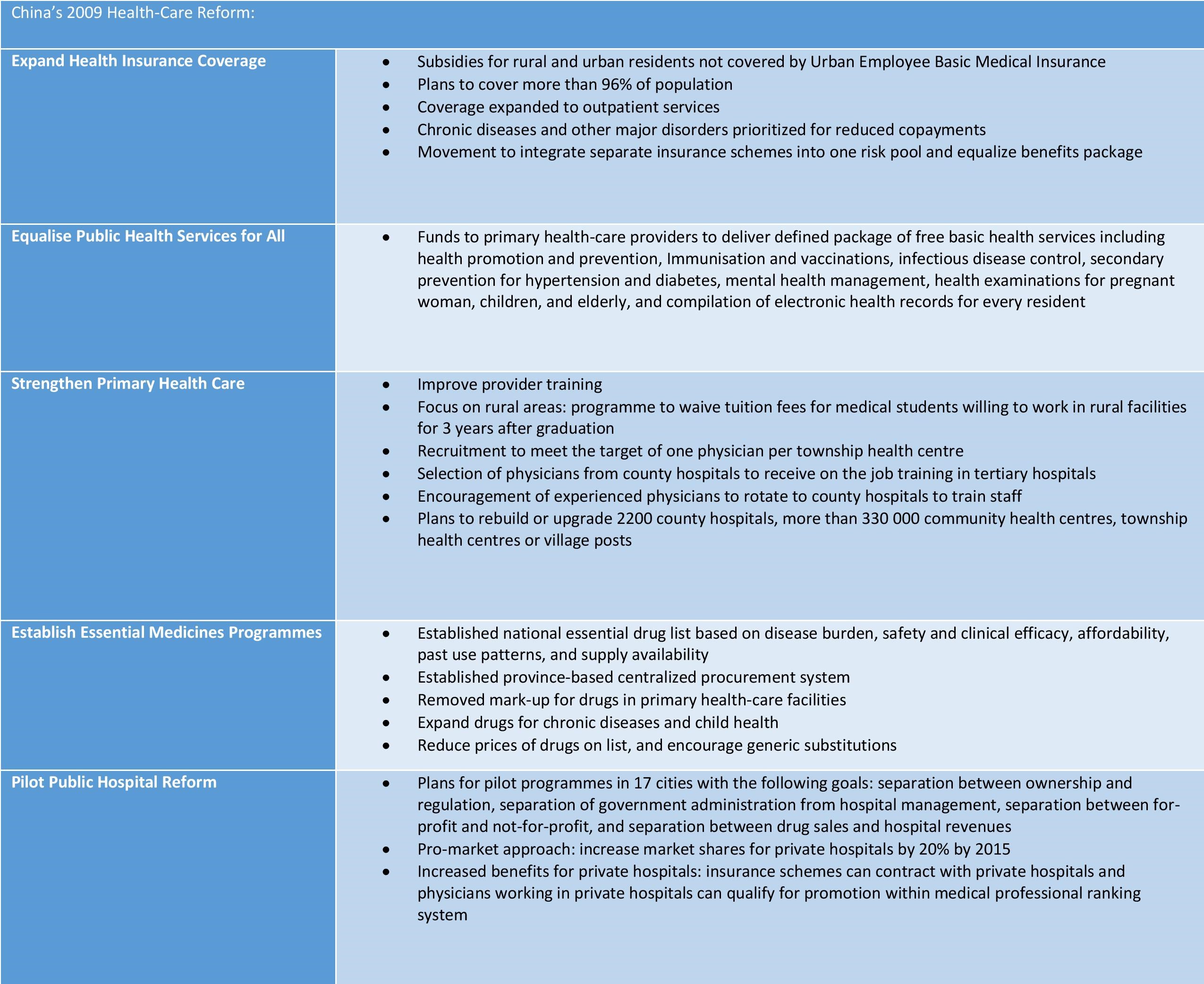

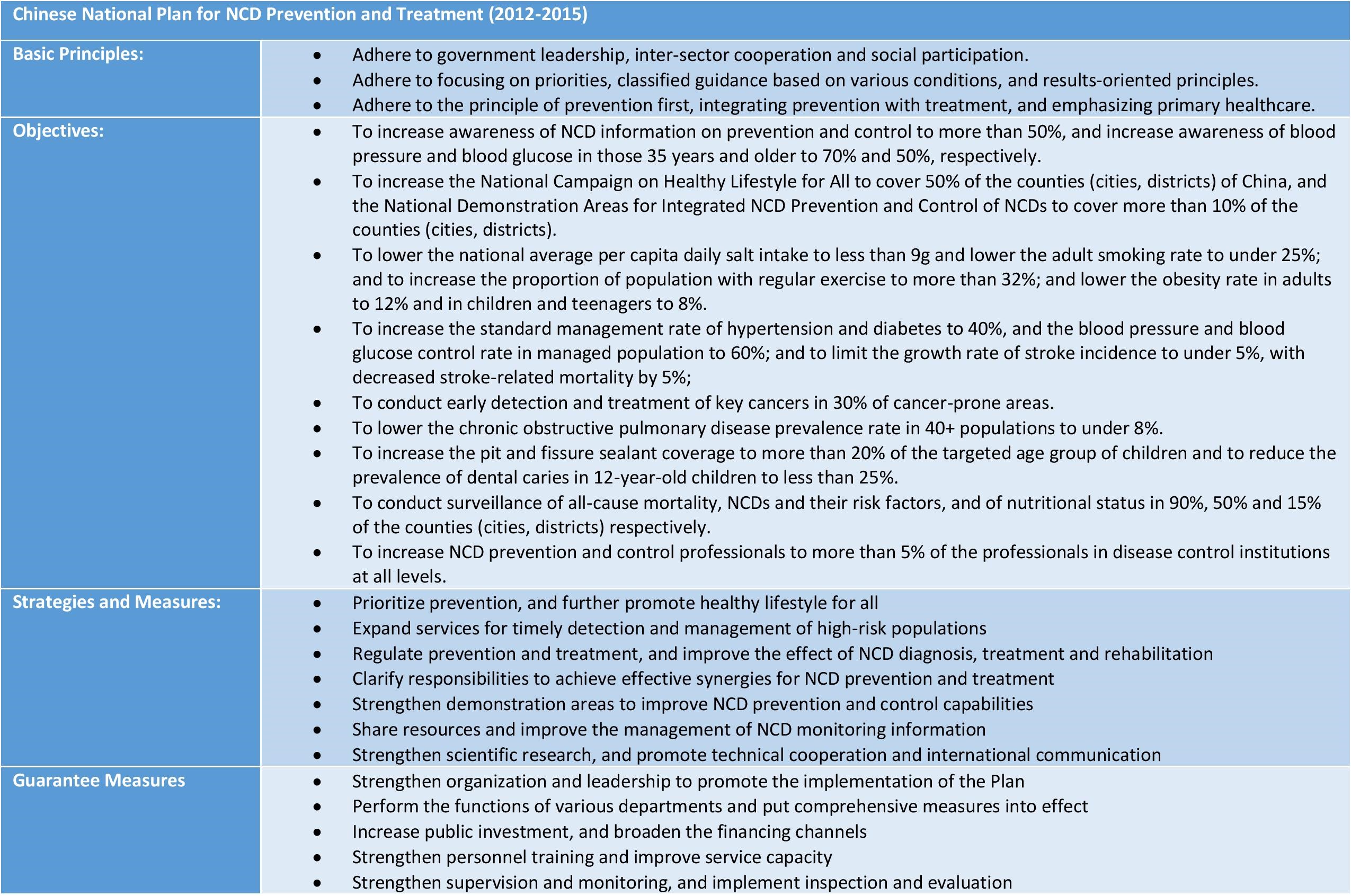

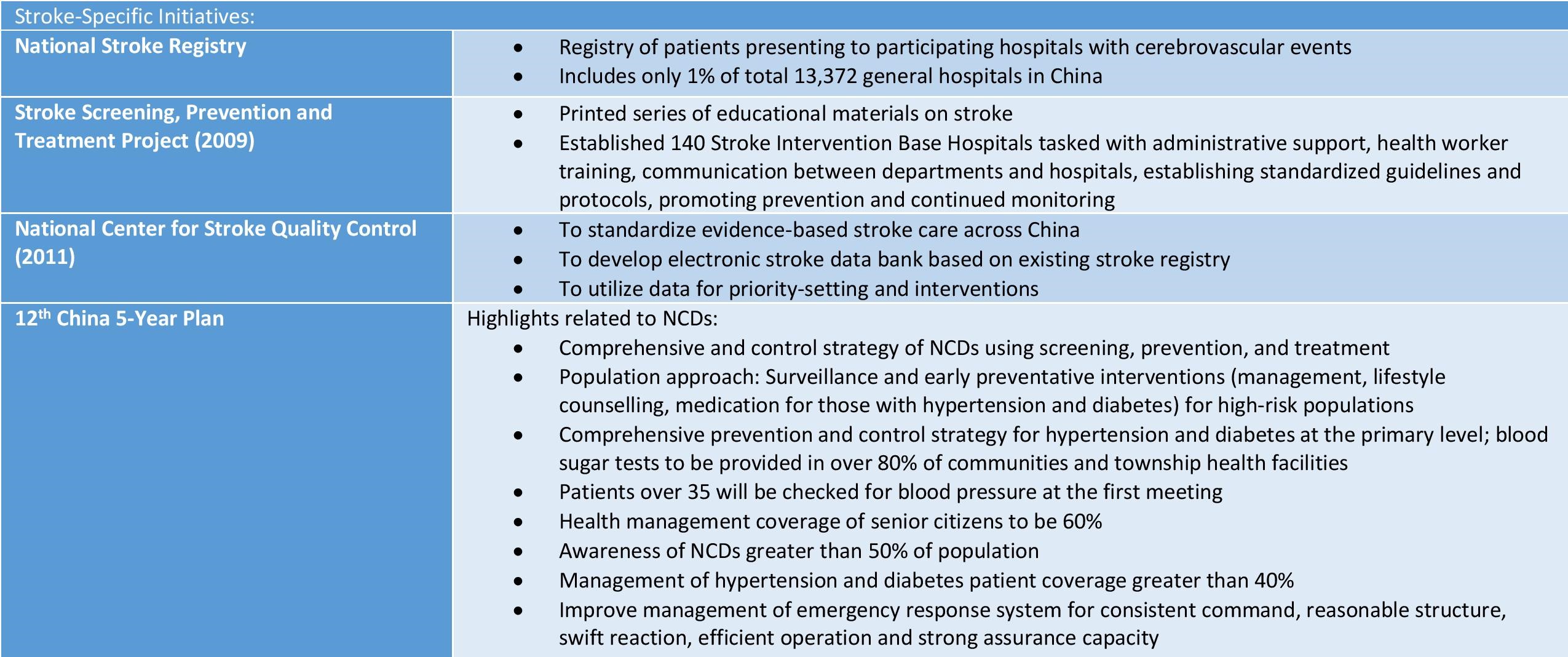

In the recent decade, China has taken appropriate first steps in priority-setting towards addressing the issue and has made great improvements to their stroke care pathway, the part of the health system related to stroke. Establishing a host of initiatives and installing a number of institutions tasked with managing different facets of stroke care, China has shown that stroke is clearly on the country’s health agenda. The Chinese National Stroke Registry which started in 2007 has been instrumental to the development of stroke surveillance by collecting stroke incidence, inhospital and post-hospital treatment data, and post-stroke outcomes from major hospitals (Liu et al. 2011). A few years later, the Stroke Screening, Prevention, and Treatment Project in 2009 and National Center for Stroke Quality Control in 2011 was established. These organizations serve a number functions from collecting patient data to improving research and health planning. The 2009 health care reforms made more general structural changes across the health care system with the goals of increasing coverage, access, and quality. At the same time, the topic of the management of noncommunicable diseases has been a major topic of recent national planning documents such as the 12th 5-Year Plan and the recent 13th 5-Year Plan (see Appendix).

The purpose of this literature review is to reveal if there are gaps between the current global standard of stroke care, that which is outlined by the WHO and Cochrane systematic reviews, and the level of stroke care as it currently exists in China. Namely, what are the challenges and barriers to implementing a stroke care pathway in China. More specifically, this will be done by investigating delays in the pathway of stroke emergencies. The stroke emergency is unique in that there are several well-defined measures for adequate care such as the recognizable “golden window” which comes from the time of effectiveness for thrombolysis to treat a stroke emergency without adverse effects (Wardlaw et al. 2014). The Cochrane Review for acute ischaemic stroke has found that thrombolytic therapy given even up to 6 hours can reduce mortality or dependence in percentage of patients (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.78-0.93), but the three-hour window offers the most overall benefit as it decreased mortality or disability (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.56-0.79) without increasing mortality (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.82-1.21) (Wardlaw et al. 2014). Therefore, it is easy to evaluate the level of adequacy of care based on whether or not this time limit is met.

End of Extract - Full Manuscript Available by Request

Figures